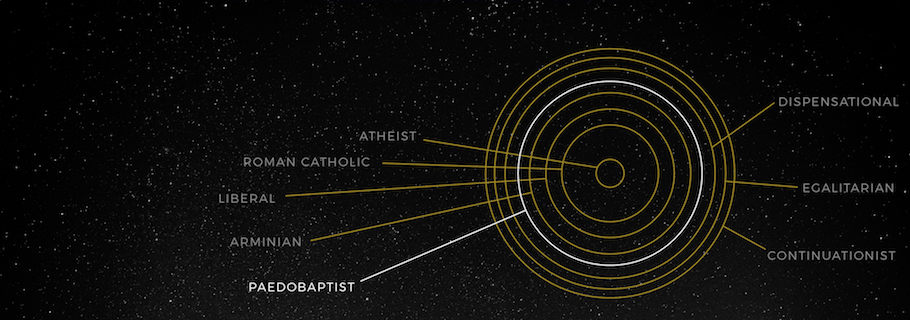

For the past few weeks I have been taking a day a week to tell how I have arrived at my various theological convictions. I’ve done this by telling you why I am not what I am not: I am not atheist, Roman Catholic, liberal, or Arminian. Today I want to tell you why I am not paedobaptist. But first, of course, definitions are in order.

While all Protestants affirm the necessity of baptism, there are two broad understandings of who should be the recipient of this act, and both are within the bounds of Christian orthodoxy. Some hold to believer’s baptism (credobaptism) and state that only those who make a credible profession of faith ought to be baptized. Others hold to infant baptism (paedobaptism) and believe that the children of believers ought to be baptized. The Westminster Shorter Catechism defends this position: “…the infants of such as are members of the visible church, are to be baptized.” The same catechism says, “Baptism is a sacrament, wherein the washing with water, in the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Ghost, doth signify and seal our ingrafting into Christ, and partaking of the benefits of the covenant of grace, and our engagement to be the Lord’s.”

By rights I ought to be a convinced paedobaptist. I was baptized in an Anglican church by parents who soon developed Presbyterian convictions. I spent most of my childhood in a Dutch Reformed church that affirmed the Heidelberg Catechism which asks, “Should infants, too, be baptized?” It answers, “Yes. Infants as well as adults belong to God’s covenant and congregation. Through Christ’s blood the redemption from sin and the Holy Spirit, who works faith, are promised to them no less than to adults. Therefore, by baptism, as sign of the covenant, they must be incorporated into the Christian church and distinguished from the children of unbelievers. This was done in the old covenant by circumcision, in place of which baptism was instituted in the new covenant.” This was my understanding of baptism as I grew up, as I transitioned into adulthood, as I married, and as I became a father.

When our first child was born, Aileen and I prepared ourselves to baptize him. But just before the day arrived, a series of events unfolded that stopped us in our tracks. It would be fourteen years before he was baptized and, even then, only after he professed faith in Christ. By that time I would be a pastor at a Reformed Baptist church. Here’s what happened.

Nick was born early in 2000 and we soon began planning a date for his baptism. However, by that time my parents had moved to the States and we wanted to wait for their next visit so they could celebrate with us. It can’t have been more than a few weeks after his birth when one of our elders, a sweet and godly man, approached us to ask about our plans. We told him that we wanted to wait until my parents could be with us. He reported back to the other elders and their reaction surprised and confused us. They communicated to us their expectation that we would baptize him right away. We loved and trusted those men, so were perplexed. Why the rush? If baptism is simply a sign and seal that communicates no saving grace, why the urgency? What difference would a few weeks make? Right here, for the first time, a hint of doubt entered my mind.

I asked the elders if they would grant us a bit of time. A week’s reflection had shown me that while I could explain infant baptism perfectly well, I couldn’t satisfactorily defend it from the Bible. I was beginning to wonder if paedobaptism was even in the Bible. The elders felt that this hesitation was a rejection of both our profession of faith and our church membership vows. It looked like Aileen and I were going to be placed under the discipline of the church.

Thankfully, we found a compromise. Right around this time I received a job offer in a distant town and, since we would soon be leaving the church anyway, I asked the elders if they would be willing to terminate our membership on that basis. They were willing, and we parted as friends. (I should add that Aileen and I were young and foolish enough that we undoubtedly handled this situation poorly at times and do not count ourselves blameless. We have nothing but love and respect for that church and its elders.)

When we moved to our new home we began attending Baptist churches. We eventually settled into one and, in order to become a member, I had to be baptized as a believer. By then my convictions had grown and deepened enough that I believed it was the right thing to do. Since that day my convictions have grown all the more.

So why am I not paedobaptist? I am not paedobaptist because, quite simply, I cannot see infant baptism clearly prescribed or described in the New Testament. I see believer’s baptism and so, too, does every paedobaptist. We agree together that we are to preach “believe and be baptized” and extend that baptism to those who have made a profession of faith. That is perfectly clear. And, indeed, Aileen was rightly baptized as an adult believer in a paedobaptist church.

The pressing question is whether the Bible calls for a second kind of baptism—the baptism of the children of believers. It is this baptism that I do not see despite my efforts to do so. The New Testament contains no explicit command to baptize the children of believers and likewise contains no explicit examples of it. (To be fair, neither does it expressly prohibit infant baptism or show a second-generation Christian being baptized as a believer.) Instead, the doctrine has to be drawn from what I understand as an unfair continuity between the old and new covenants and from assuming that children were part of the various household baptisms (Acts 16:15; 18:8; 1 Corinthians 1:16). I suppose I am credobaptist rather than paedobaptist for the very reason most paedobaptists are not credobaptists: I am following my best understanding of God’s Word. My position seems every bit as obvious to me as the other position seems to those who hold it. What an odd reality that God allows there to be disagreement on even so crucial a doctrine as baptism. What a joy, though, that we can affirm that both views are well within the bounds of orthodoxy and that we can gladly labor together for the sake of the gospel.

If you have never considered your position or the opposite one, consider reading or listening to this exchange between R.C. Sproul and John MacArthur. While affirming mutual love and respect, they each defend their position very well. It is a model of friendly disagreement on an issue that is important, but not critical.