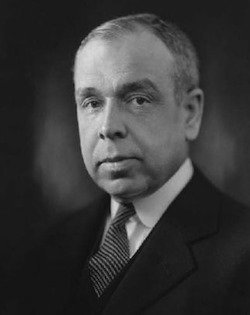

Today we begin a new round of Reading Classics Together; over the next 7 weeks we will be reading through Gresham Machen’s classic work Christianity & Liberalism. Everyone is welcome to join us as we do so. The assignment today was simply to read the Introduction (only 10 pages); from this point forward we will be reading one chapter per week until the book is complete. Each week I will jot down a few thoughts about the book and will then leave the comments open so you can share what you’ve learned, ask your questions, and offer your reflections.

Introduction

Christianity & Liberalism, like all books, is set in a specific context. In this case the context is the early decades of the 20th century when liberalism was rising and opposing traditional Protestant Christianity. Here is how Machen later described his purpose in writing this book:

Christianity & Liberalism, like all books, is set in a specific context. In this case the context is the early decades of the 20th century when liberalism was rising and opposing traditional Protestant Christianity. Here is how Machen later described his purpose in writing this book:

I tried to show that the issue in the Church of the present day is not between two varieties of the same religion, but, at bottom, between two essentially different types of thought and life. There is much interlocking of the branches, but the two tendencies, Modernism and supernaturalism, or (otherwise designated) non-doctrinal religion and historic Christianity, spring from different roots. In particular, I tried to show that Christianity is not a “life,” as distinguished from a doctrine, and not a life that has doctrine as its changing symbolic expression, but that—exactly the other way around—it is a life founded on a doctrine.

Part of the challenge in reading such a book is in filtering the issues that were relevant only or largely in a specific historical context from those that remain relevant today. At one point Machen has a lot to say about education and about how some states are forbidding anything other than a public school education. Today, of course, any state allows a public education or a Christian, private or home education. While this situation may arise again in the future, for now it is not an imminent concern.

It is immediately obvious how this book will be relevant to us today. We live in an era that has been heavily impacted by liberalism and we live at a time when Christians continue to grapple with the relationship of faith to science. The questions and concerns of the early 20th century remain concerns today which means that biblically-based answers from the 20th century will be just as relevant for the 21st century.

Now, let me share a few of the things that stood out to me in this chapter.

In the first place, I latched on to this quote: “In the sphere of religion, as in other spheres, the things about which men are agreed are apt to be the things that are least worth holding; the really important things are the things about which men will fight.” The reality of living in a sinful world is that all of us are wrong about certain matters. When we find things worth fighting about, whether that is outright combat or respectful discussion, we do well to realize that those may well be the most important things.

Of course the time in which Machen was writing was a time of great conflict–a conflict over the very essence of the Christian faith. One of the complicated parts of the whole battle is that both sides were using traditional Christian terminology but in very different ways. On the one hand were the traditional Christians while on the other were the “modern naturalistic liberals” who denied “the entrance of the creative power of God (as distinguished from the ordinary course of nature) in connection with the origin of Christianity.”

Liberalism was an attempt to solve this problem: What is the relation between Christianity and modern culture; may Christianity be maintained in a scientific age? The liberal theologian was attempting to rescue Christianity from its supposed conflict with science. To do this it eschewed any kind of supernaturalism and replaced it with naturalism. Machen says that in so doing modern liberalism can be criticized for being both un-Christian and unscientific; in attempting to rescue the faith from science it actually does damage to both faith and science. Ironic that. In this book Machen looks only to the first line of criticism so he can show how liberalism is un-Christian.

Our principal concern just now is to show that the liberal attempt at reconciling Christianity with modern science has really relinquished everything distinctive of Christianity, so that what remains is in essentials only that same indefinite type of religious aspiration which was in the world before Christianity came upon the scene. In trying to remove from Christianity everything that could possibly be objected to in the name of science, in trying to bribe off the enemy by those concessions which the enemy most desires, the apologist has really abandoned what he started out to defend. Here as in many other departments of life it appears that the things that are sometimes thought to be hardest to defend are also the things that are most worth defending.

How serious are the theological implications of liberalism? Really serious, according to Machen. “If a condition could be conceived in which all the preaching of the Church should be controlled by the liberalism which in many quarters has already become preponderant, then, we believe, Christianity would at last have perished from the earth and the gospel would have sounded forth for the last time.”

Let me close with what is a kind of purpose statement for this book:

The Christian religion which is meant is certainly not the religion of the modern liberal Church, but a message of divine grace, almost forgotten now, as it was in the middle ages, but destined to burst forth once more in God’s good time, in a new Reformation, and bring light and freedom to mankind. What that message is can be made clear, as is the case with all definition, only by way of exclusion, by way of contrast. In setting forth the current liberalism, now almost dominant in the Church, over against Christianity, we are animated, therefore, by no merely negative or polemic purpose; on the contrary, by showing what Christianity is not we hope to be able to show what Christianity is, in order that men may be led to turn from the weak and beggarly elements and have recourse again to the grace of God.

Next Week

For next week please read chapter 2 which is titled “Doctrine.” Then return here on Thursday and we can talk it over.

Your Turn

The purpose of this program is to read these books together. So if you have something to say, whether a comment or criticism or question, feel free to use the comment section for that purpose.

Note: If you are mentioning Reading Classics Together on Twitter, we’ve got the hashtag #rctmachen set aside for that purpose.