A few weeks ago I set out on a new series of articles through which I am scanning the history of the church—from its earliest days all the way to the present time—to examine some of Christianity’s most notorious false teachers. Along the way we have visited such figures as Arius, Pelagius, Joseph Smith, and Ellen G. White. As we move steadily closer to contemporary times we must pause to take a brief look at the life and ministry of Harry Emerson Fosdick, the foremost proponent and popularizer of theological liberalism.

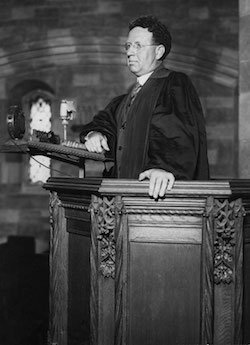

Harry Emerson Fosdick

Harry Emerson Fosdick was born in Buffalo, New York, on May 24, 1878. As a young boy he claimed to have been born again, but even as a teenager rebelled against the “born again” movement known as fundamentalism. He developed an early interest in theology and chose to pursue ministerial training at Colgate Divinity School where he was influenced by William Newton Clarke, an early advocate of the social gospel. Upon graduating from Colgate he continued to Union Theological Seminary. In 1904 he accepted his first pastorate at First Baptist Church in Montclair, New Jersey, and four years later also accepted a faculty position at Union where he was to teach until 1946. Fosdick quickly proved himself a skilled communicator and compelling speaker and it would not be long before he would be known as America’s foremost minister.

Harry Emerson Fosdick was born in Buffalo, New York, on May 24, 1878. As a young boy he claimed to have been born again, but even as a teenager rebelled against the “born again” movement known as fundamentalism. He developed an early interest in theology and chose to pursue ministerial training at Colgate Divinity School where he was influenced by William Newton Clarke, an early advocate of the social gospel. Upon graduating from Colgate he continued to Union Theological Seminary. In 1904 he accepted his first pastorate at First Baptist Church in Montclair, New Jersey, and four years later also accepted a faculty position at Union where he was to teach until 1946. Fosdick quickly proved himself a skilled communicator and compelling speaker and it would not be long before he would be known as America’s foremost minister.

In 1919 Fosdick was asked to become associate pastor at First Presbyterian Church in New York City, though he was allowed to retain his baptistic convictions. He quickly gained a reputation as a leading Christian voice, and hundreds and then thousands descended on First Presbyterian to hear his sermons. It was here, on May 21, 1922, that he preached the sermon that came to define him: “Shall the Fundamentalists Win?” In this sermon he proclaimed that there was a great battle in the church between the fundamentalists and the modernists or liberals, and that he was going to stand firmly on the side of the liberals. Because of his desire to modernize the Christian faith, he soundly rejected belief in a series of traditional Christian doctrines including Christ’s virgin birth, the inerrancy of Scripture, and the literal return of Jesus Christ. He decried the fundamentalists as being intolerant for demanding adherence to doctrines that science, reason, and a modern world could no longer sustain. John D. Rockefeller enjoyed this sermon so much that he had 130,000 copies printed and mailed to every Protestant pastor in the nation.

“Shall the Fundamentalists Win?” set off what would soon be called the Fundamentalist-Modernist controversy. We need to be clear that we cannot import into this battle a twenty-first century understanding of fundamentalism. When Fosdick battled the fundamentalists of his day, he battled nothing less than traditional or conservative Christianity. Fundamentalists were those who insisted upon the key tenets of historic, orthodox Christianity—what they defined as the fundamental doctrines of the faith.

Fosdick was by no means the only liberal theologian of his day, but he was the one to gain the widest acclaim and the broadest platform. While many others were pressing theological liberalism in the seminaries and the halls of academia, Fosdick was on the radio waves and in the bookstores, taking his message to the common people. His voice extended through his radio program, The National Vespers Hour, which was broadcast in the Northern and Eastern United States, and through many bestselling books which eventually sold in the millions. On two separate occasions he was on the cover of TIME magazine.

By the mid 1920’s Fosdick had established himself as the leading voice of twentieth-century liberalism. His stand for liberalism put him at odds with many of the conservative voices in Presbyterianism, and this led him to leave First Presbyterian Church in 1925 and to go instead to Park Avenue Baptist Church.

I am a heretic if conventional orthodoxy is the standard. I should be ashamed to live in this generation and not be a heretic.

In the early 1920’s, J. Gresham Machen emerged as one of the foremost opponents of liberalism. His 1923 book Christianity and Liberalism was a strong, biblical response that drew comparisons between the Bible and liberal theology and showed that the two were in clear opposition. He rightly asked, “The question is not whether Mr. Fosdick is winning men, but whether the thing to which he is winning them is Christianity.” Others joined the battle as well. Fosdick remained firm in the face of such attacks, declaring, “They call me a heretic. Well, I am a heretic if conventional orthodoxy is the standard. I should be ashamed to live in this generation and not be a heretic.”

In 1929, Princeton, once a bastion of Reformed thinking and teaching, was reorganized under modernist influences. Almost immediately four Princeton professors who held to the Reformed faith (Robert Dick Wilson, J. Gresham Machen, Oswald T. Allis, and Cornelius Van Til) withdrew from Princeton and established Westminster Theological Seminary in Philadelphia in order to continue upholding the faith Princeton once defended. If the Fundamentalist-Modernist controversy was begun with Fosdick’s sermon in 1922, it was effectively cut off among conservative churches in 1929 with the departure of those professors.

Rockefeller money soon built a grand new building on the Hudson, and in 1930 Fosdick was installed as pastor at Riverside Church. He would pastor this congregation for sixteen years, and, after his retirement, attend it for a further twenty-eight. This church became his laboratory for liberalism and it was here that he practiced his liberal values to the full. (To be fair, and to give credit where credit is due, he was a strong advocate of racial reconciliation and was perhaps the most notable preacher to invite African-American preachers into his pulpit.)

Fosdick died in New York City on October 5, 1969, two weeks after being hospitalized for a heart attack. He was ninety-one years old.

False Teaching

Harry Emerson Fosdick was not an original thinker as much as a popularizer who took the theory of liberalism from the seminaries and brought it to a common level. He wanted to modernize the faith by making it attractive to, and compatible with, modern times and modern sensibilities. At heart, liberalism questioned the nature of the Bible and denied its inerrancy, infallibility, and authority. Liberalism denied that the Bible is the Word of God and insisted instead that it contains the Word of God. Once Scripture’s authority had been denied, a host of doctrines would necessarily fall in its wake.

Fosdick questioned the essential beliefs necessary to be a Christian and began to challenge long-held, orthodox Christian beliefs such as the virgin birth, and the return of Christ Jesus. Robert Moats Miller, one of Fosdick’s biographers, wrote, “Fosdick could not believe that Jesus was virgin born. He did not ridicule those who did, but he was adamant that such belief was not essential to acceptance of Christian faith. … Fosdick doubted whether Jesus ever thought of himself as the Messiah; perhaps he did, but more probably Jesus’ disciples may have read this into his thinking.” He also denied the wrath of God, suggesting that wrath was simply a metaphor for the natural consequences of doing wrong. With wrath removed, it was inevitable that the substitutionary atonement of Jesus Christ would also be denied. Before long Fosdick’s Christianity looked nothing like historic Christianity.

In a later sermon, “The Church Must Go Beyond Modernism,” Fosdick spoke of his methodology in modernizing the Christian faith, saying, “We have already largely won the battle we started out to win; we have adjusted the Christian faith to the best intelligence of our day and have won the strongest minds and the best abilities of the churches to our side. Fundamentalism is still with us but mostly in the backwaters. The future of the churches, if we will have it so, is in the hands of modernism.” Of course, he was too optimistic, and too blinded by his own success. Liberalism posed a major challenge to the faith, but like all other challengers, it would rise and then wane.

Followers and Modern Adherents

If Fosdick was the man who popularized and legitimized liberalism, we can rightly say that subsequent liberals, and especially those who operated at the popular level, followed in his footsteps. Men like Norman Vincent Peale, Robert Schuller, and John Shelby Spong are among them. Martin Luther King Jr., a theological liberal in his own right, regarded Fosdick as the greatest preacher of the century and in 1958, inscribed a copy of Stride Toward Freedom for Fosdick with these words: “If I were called upon to select the foremost prophets of our generation, I would choose you to head the list.”

But Fosdick’s influence extends farther than that. Though the Fundamentalist-Modernist controversy began within Presbyterianism, it soon spread to other Protestant denominations, eventually leading to today’s division between “mainline” and “evangelical” Protestant churches. About half of today’s mainline Protestants consider themselves liberal, and they, too, whether they know it or not, are influenced by Fosdick.

What the Bible Says

Fosdick’s teaching was false in many areas, but the heart of it all was his denial of the inerrancy, infallibility, and authority of the Bible. He elevated human reason above the plain words of Scripture; he made reason the final arbiter of truth. All the other doctrines he denied depended upon first undermining the Bible. Christians have long insisted, as the fundamentalists did in his day, that God’s Word, not science or human reason, is the measure of true knowledge. Proverbs 3:5-7 says, “Trust in the LORD with all your heart, and do not lean on your own understanding. In all your ways acknowledge him, and he will make straight your paths. Be not wise in your own eyes; fear the LORD, and turn away from evil.” Our understanding of ourselves and the world around us is flawed; we must depend upon God to reveal true knowledge.

If we remove the offense of the gospel, we have removed the power of the gospel.

In his second letter to Timothy, Paul warned, “For the time is coming when people will not endure sound teaching, but having itching ears they will accumulate for themselves teachers to suit their own passions, and will turn away from listening to the truth and wander off into myths” (2 Timothy 4:3-4). Fosdick wanted to make the Christian faith soothing to those itching ears and, in so doing, distorted it beyond all recognition. The reality is that the Christian faith is, and always will be, offensive. If we remove the offense of the gospel, we have removed the power of the gospel.

Paul’s words to the Corinthians are perfectly suited to Fosdick and his liberalism:

Where is the one who is wise? Where is the scribe? Where is the debater of this age? Has not God made foolish the wisdom of the world? For since, in the wisdom of God, the world did not know God through wisdom, it pleased God through the folly of what we preach to save those who believe. For Jews demand signs and Greeks seek wisdom, but we preach Christ crucified, a stumbling block to Jews and folly to Gentiles, but to those who are called, both Jews and Greeks, Christ the power of God and the wisdom of God. For the foolishness of God is wiser than men, and the weakness of God is stronger than men.

(1 Corinthians 1:20-25)