A few months ago I set out on a series of articles through which I am scanning the history of the church—from its earliest days all the way to the present time—to examine some of Christianity’s most notable false teachers and to examine the false doctrine each of them represents. Along the way we have visited such figures as Joseph Smith (Mormonism), Ellen G. White (Adventism), Norman Vincent Peale (Positive Thinking), and Benny Hinn (Faith Healing). Today we turn to a man who helped lead the Emerging Church and who was once named by TIME as one of the 25 Most Influential Evangelicals in America.

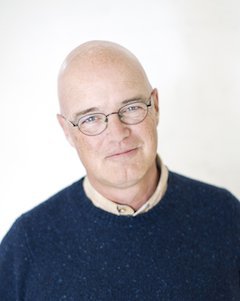

Brian McLaren

Brian McLaren (born in 1956) studied humanities at the University of Maryland and graduated with graduate and post-graduate degrees in English. Beginning in 1978, he taught college-level English, before founding Cedar Ridge Community Church in 1986. He served this church as its founding pastor until 2006, when he handed off the role so he could focus on writing and public speaking.

Brian McLaren (born in 1956) studied humanities at the University of Maryland and graduated with graduate and post-graduate degrees in English. Beginning in 1978, he taught college-level English, before founding Cedar Ridge Community Church in 1986. He served this church as its founding pastor until 2006, when he handed off the role so he could focus on writing and public speaking.

In 1986 Zondervan released McLaren’s first book, The Church on the Other Side: Doing Ministry in the Postmodern Matrix. This book established him as a leader and thinker in the church at a time when Christians were attempting to grapple with the dawning reality of postmodernism.

However, it was his 2001 work of fiction, a New Kind of Christian, that introduced him to the wider church and earned him Christianity Today’s Award of Merit in 2002. It was the first volume in a trilogy and quickly became one of the foremost texts for what was soon known as the Emerging Church movement. A New Kind of Christian tells the story of Dan Poole, a pastor who finds himself ready to give up on Christian ministry. Increasingly disillusioned, he has become less and less certain about what he believes. When he takes his daughter to a concert he meets Neil Oliver, a high school science teacher, and together they discuss a long list of core Christian doctrines. According to the publisher, “This stirring fable captures a new spirit of Christianity—where personal, daily interaction with God is more important than institutional church structures, where faith is more about a way of life than a system of belief, where being authentically good is more important than being doctrinally ‘right,’ and where one’s direction is more important than one’s present location.” McLaren became known as a Christian leader who was talking about life and faith in ways that seemed new and fresh.

McLaren followed this book with many more—nearly twenty to date. The two most noteworthy of his books have probably been A Generous Orthodoxy which he calls “a personal confession and a manifesto of the emerging church conversation” and A New Kind of Christianity in which he offers responses to “ten questions that are central to the emergence of a postmodern, post-colonial Christian faith.”

In 2005 McLaren was named by TIME as one of the 25 Most Influential Evangelicals in America under the heading “Paradigm Shifter.” They pointed to his ambiguous statements about gay marriage and said that he represented a kinder and gentler form of Christianity. The following year he joined with Tony Campolo, Jim Wallis, Richard Rohr, and others to found Red Letter Christians, an organization dedicated to seeing Christianity liberated from both right-wing and left-wing politics in America. Where Christianity has been dominated for too long by discussions of abortion and homosexuality, this movement prefers to look to the words Jesus spoke and focus on issues related to social justice.

McLaren has traveled the world as a teacher, preacher, lecturer, and conference speaker, and has been granted honorary degrees from both Carey Theological Seminary and Virginia Theological Seminary. In September 2012 he made headlines for participating in a gay marriage ceremony for his son Trevor and his partner Owen Ryan. The wedding was officiated by a Universal Life minister, with McLaren leading a commitment ceremony built around Christian themes.

False Teaching

As McLaren’s theology has matured and taken shape over time and through his books, he has stepped forward as a leader in a new and revived form of theological liberalism. This displays itself most clearly in his view of Scripture.

In A New Kind of Christianity he insists that Christians have long been reading the Bible through the distorted lens of a Greco-Roman narrative. This narrative produced many false dualisms, an air of superiority, and a false distinction between those who were “in” and those who were “out.” These three marks of false narrative have so impacted our faith that we can hardly see past them. His book attempts to do that, and to reconstruct the Christian faith as it is meant to be.

Leading the way is his view of the Bible. He does not see the Bible as God’s inspired, inerrant, infallible, authoritative Word. He displays this, for example, in his interpretation of the account of Noah by saying, “a god who mandates an intentional supernatural disaster leading to unparalleled genocide is hardly worthy of belief, much less worship” (A New Kind of Christianity).

He goes on to say, “I’m recommending we read the Bible as an inspired library. This inspired library preserves, presents, and inspires an ongoing vigorous conversation with and about God, a living and vital civil argument into which we are all invited and through which God is revealed” (New Kind). After all, “revelation doesn’t simply happen in statements. It happens in conversations and arguments that take place within and among communities of people who share the same essential questions across generations. Revelation accumulates in the relationships, interactions, and interplay between statements.” He understands the Bible to be a slowly-evolving human understanding of God. “Scripture faithfully reveals the evolution of our ancestors’ best attempts to communicate their successive best understandings of God. As human capacity grows to conceive of a higher and wiser view of God, each new vision is faithfully preserved in Scripture like fossils in layers of sediment.”

This is nothing less than theological liberalism in twenty-first century, post-modern clothing (which is why Gresham Machen’s Christianity and Liberalism offers a rebuttal, though it was written 90 years earlier). Like Fosdick and other liberals before him, McLaren has assumed authority over the Bible instead of placing himself under its authority. His understanding of Scripture frees him to see Christian doctrine as evolving, and himself as an instrument of this evolution. In this way he revisits and reinterprets whatever does not accord with modern sensibilities. He has denied the literal nature of hell along with its eternality; he has denied the substitutionary atonement of Jesus Christ; he has denied Jesus Christ as the only way to the Father; he has affirmed homosexuality as good and pleasing to God. And he continues to think and to write, meaning that his theological development is not yet complete.

Followers and Adherents

McLaren has long been a leader in the Emerging Church, and almost all of those who “emerged” with him have known his influence. So too have many of his fellow progressive Christians. He continues to have a broad speaking platform and to write popular books.

What the Bible Says

The Bible insists that it is the living and active Word of God, breathed out by God himself. It is not a man-made document subject to error, evolution, antiquation, or reinterpretation. Jesus himself spoke clearly about the authority and relevance of Scripture, and showed no hesitation in unfolding its meaning and faulting others for misunderstanding it. In Mark 12:24, “Jesus said to them, ‘Is this not the reason you are wrong, because you know neither the Scriptures nor the power of God?’” He declared, “Scripture cannot be broken” (John 10:35).

Where McLaren casts doubt on the idea that we can ever really confidently know and understand the Bible, Christians have long held that God spoke and inspired his prophets and apostles to write because he actually intended to be heard as saying something, and that the message would be carried on and be understood forever after (see 2 Peter 1:16-21). This is why Jude calls it “the faith that was once for all delivered to the saints” (Jude 3), and why Paul is so emphatic with Timothy that he “guard the good deposit entrusted to [him]” (2 Timothy 1:14). Kevin DeYoung says it well in Taking God at His Word: “The Bible is an utterly reliable book, an unerring book, a holy book, a divine book. … There is no more authoritative declaration than what we find in the word of God, no firmer ground to stand on, no ‘more final’ argument that can be spoken after Scripture has spoken.”