If you are a committed reader, you know what it’s like when you get swept away by a book—where hours pass in what feels like minutes. You know the sheer pleasure of being drawn into a book that is unexpectedly interesting and intriguing. This was the case for me this weekend when I began to read The Temple and the Tabernacle: A Study of God’s Dwelling Places from Genesis to Revelation. Hidden behind that title is a brilliant and fascinating work that offers something to every Christian.

This book, as the title suggests, is a study of the Old Testament temple and tabernacle. Yet it is much more than that. So central are these buildings to Old Testament worship and New Testament symbolism that understanding them, understanding the roles they played, understanding the way they were made, understanding their function to Old Testament worship, and understanding the key differences between them illumines so much of the Christian faith. We better understand who we are when we understand these buildings.

Hays begins in the Garden of Eden which so many scholars understand as its own kind of temple. “The garden … is a place where God’s presence dwells in a special kind of way so that his people can be with him and worship him. This is precisely the function of a sanctuary or temple.” The garden, then, is a tabernacle before the tabernacle, a temple before the temple. It is here that we first encounter the notion of God dwelling among his people, of the symbolic trees that may have found their way into both the tabernacle and temple, of sin and the interruption of relationship between God and man, of the cherubim that were so prominent within the two buildings.

He then moves to the wilderness between Egypt and Canaan and describes the creation and the function of the tabernacle. “The tabernacle is the avenue through which God will encounter his people. It is the means to an end; it is not the end itself. The goal is for God’s people, the ones he has just delivered, to enter into relationship with him and experience his presence.” Each element of that tabernacle and each action carried out there is meant to permit and promote the relationship of God to his people. Of course he shows how the tabernacle prefigures Christ, but he offers an appropriate and much-needed caution: “Without doubt there is much about the tabernacle that points to Christ and finds ultimate fulfillment in Christ. Yet … Just because there is a central story-line theological connection between Christ and the ancient tabernacle, we do not have the liberty to let our imaginations run wild and dream up prophetic connections about every little detail of the tabernacle. This is not at all the kind of comparison the New Testament makes, and we should seek to follow the approach the New Testament takes in relating Christ to the tabernacle.”

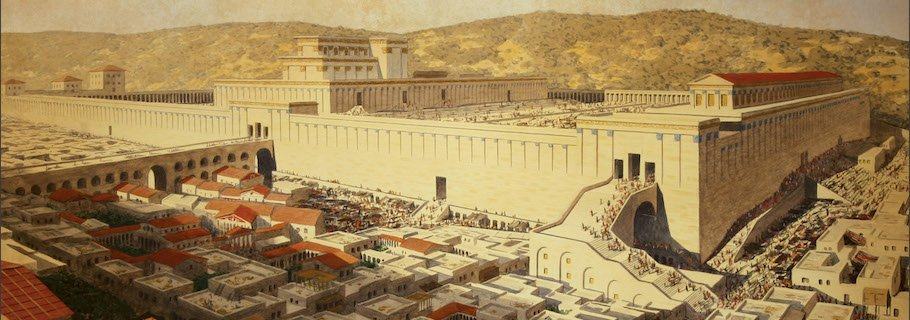

With the Garden of Eden and tabernacle behind him, he moves to Solomon’s temple and carefully shows how this temple is different from the tabernacle, not only in its size, grandeur, and permanence, but also in its planning and building. “The clear and unmistakable focus throughout the tabernacle construction story in Exodus 25–31 and in Exodus 35–40 is on constructing the tabernacle exactly as God has explicitly and verbally commanded the Israelites to construct it. God initiates the construction of the tabernacle, he gives explicit instructions on how to construct it, he demands total obedience to the details he provides, and he empowers the workmen with the skill needed to carry out the work. From start to finish, it is a work conceived, designed, and superintended by God.” But then we see this important contrast: “Although it follows the same basic literary structural form, the account of the construction of the temple in 1 Kings 5–8 is dramatically different. The contrast is startling. God is not involved. He does not initiate the construction of the temple, give any design input, or superintend the construction. Indeed, instead of being dominated by God and his verbal directives, the temple construction story is dominated by King Solomon and two Canaanites from Tyre.” As the temple is completed, we see that God still comes to dwell within it, but in a less significant way than the tabernacle.

Of course Solomon’s temple is destroyed after just a few hundred years, so Hays discusses the second temple, showing that while it eventually becomes one of the wonders of the ancient world, it is never God’s dwelling place in the same way as the first temple and tabernacle before it. Rather, the weight of Scripture turns to Christ as the ultimate fulfillment of the many promises that God will dwell with man. Then, of course, Hays has to look at Christians as those who today are called God’s temple. “It is rather sobering, then, and also a little frightening, to realize that if we are Christians and have accepted Jesus Christ by faith, this same holy, awesome, powerful King of the universe now resides right inside of us. This can only happen because Jesus Christ has made us holy. Because of what Jesus has done, the multiple layers of separation (courtyard, holy place, most holy place) have all been removed, and we are now allowed right into the presence of God. This is an incredible privilege, but it brings responsibility with it as well. Peter quotes from Leviticus (11:44, 45; 19:2), ‘Be holy, because I am holy,’ to challenge Christians to realize the amazing privilege they now have in Christ and thus to lead holy lives (1 Pet. 1:15–16).”

The Temple and the Tabernacle is as good a book as I’ve read in 2016 and it is one I gladly commend to you. While its focus is on ancient construction projects, ancient buildings, ancient rites, there is application for each of us today. You cannot read it without being impressed by the unity of Scripture. You cannot read it without being struck by the holiness, patience, and mercy of God. You cannot read it without seeing the insufficiency of the temple and the all-sufficiency of Christ, the one who would be the ultimate temple. Those ancient buildings were places of worship for the Israelites. Understanding them is an opportunity for worship for Christians today.