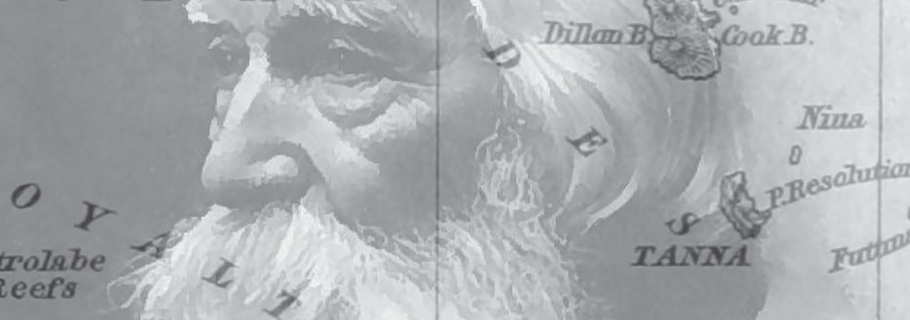

There are some figures who tower over the history of the Christian faith. They are marked by their courage, their godliness, and their sheer faithfulness. There are many missionaries in this number and John Paton must rank high among them. Few have carried out a more difficult, costly, or perilous ministry. Few have suffered to the degree that he did. Few have seen so many won to Christ. His story is now told anew in Paul Schlehlein’s John G. Paton: Missionary to the Cannibals of the South Seas.

Schlehlein, himself a missionary to the Tsongas in rural South Africa, offers four reasons for preparing his book. First, he wishes to contrast Paton’s indomitable courage and indefatigable moxie with the “diplomacy and emotional sensitivity” that marks the world and, indeed, the church today. Second, he believes Paton’s pen can arrest today’s audience as it did more than a century ago. For this reason, Schlehlein often allows Paton to speak in his own words. Third, he means to encourage missionaries and gospel workers who are fainthearted and weary with their task. He hopes that when such readers learn what God did among the cannibals of the South Seas they will be encouraged to press on in their own work. Finally, he is convinced there are crucial lessons to draw from Paton’s life. For this reason, only half of the book is biography while the rest is dedicated to lessons the biography displays.

John Paton was born in Dumfries, Scotland, on May 24, 1824, the son of Scots Presbyterian parents. Though he and his many siblings grew up in economic poverty, they were spiritually rich with parents who loved and honored the Lord and who faithfully raised their children in his discipline and instruction. Though from a young age John had to work to help support his family, he was able to receive some education and, with it, to begin evangelistic work. Eventually he was able to attend seminary and receive a theological education. It was not long before he became convinced God had called him to be a missionary to the South Seas. Yet he faced unexpected difficulty, for many of the Christians around him (though not his parents) contested the idea: “In unison, pastors and parishioners alike offered a number of arguments against such a foolhardy task. Let the reader here take note: the criticisms the church gave sound ‘spiritual’ in every way. One can even assume they attached a slew of proof texts in support.”

Paton was unswayed and arrived in the New Hebrides on November 5, 1858, accompanied by his teenaged bride and their infant son. This was known as a particularly dangerous area for it was populated with cannibals who had already shed much missionary blood. Within six months both mother and son had died from disease and Paton was left alone. Despite a double-blow that might have ended the ministry of a lesser man, he pressed on in his work. In fact, he labored there for decades, eventually accompanied by his second wife, Margaret. He lived to reap a great harvest of souls with almost entire populations coming to faith in Christ. The world is not worthy of such men.

Schlehlein aptly tells Paton’s story and then, through several chapters, focuses on a number of key lessons from his life. One chapter looks at his family and especially the ways in which he and Margaret nurtured their children in the Lord. Next, he turns to Paton’s understanding of calling, showing his conviction that all Christians are called to preach the gospel, though some are called to do it vocationally. His indomitable courage receives a chapter-length treatment as does his theology of risk, his strategy for spreading the good news of Jesus Christ, and the Calvinistic beliefs that fueled his evangelism.

Paton’s story is powerful and is worthy of a new telling. Schlehlein has done the church a great service in telling it again and telling it well, for “just as stars shine brightest in a moonless sky, the grace of the Lord Jesus flashes most brilliantly before the man-eaters of the New Hebrides.”