It is more than a little ironic, and more than a little disturbing, that some of the most prominent “Christian” scholars in the world are not Christian at all. At least, not by a definition that would require their assent to the doctrines outlined in the historic creeds and confessions. To the contrary, many of the most significant scholars at the most significant universities tend to deny the doctrines of the Trinity, of the divinity of Jesus Christ, of his virgin birth, of his atoning death, and of his resurrection. Their interest in Christianity is often more in undermining or deconstructing it than in teaching or defending it.

This is exactly the case with Karen King, long-time Hollis Professor of Divinity at Harvard University—the oldest endowed chair in the United States (1721) and undoubtedly one of its most distinguished. She has committed her career to studying the Gnostic gospels and to attempting to show how they are not only consistent with the established biblical canon, but even superior. A feminist as much as a theologian, King has had a special interest in attempting to prove that these books were suppressed by the early church precisely because they challenged the patriarchy. She is known for her interpretation of The Gospel of Mary of Magdala in which she describes Mary Magdalene as not merely a disciple of Jesus, but as his chief disciple and closest confidante. She is also known for her role in the infamous Jesus Seminar. As a protégé of its founder Robert Funk, King had her place in a group of scholars that took it upon itself to determine which of the deeds and sayings attributed to Jesus were genuine and which were not.

But more recently she has become known for her involvement in the hoax known as The Gospel of Jesus’s Wife. This hoax, and the scandal it caused, is the subject of a new book by Ariel Sabar titled Veritas: A Harvard Professor, a Con Man and the Gospel of Jesus’s Wife. It is, in a sense, the story of three obsessions—King’s obsession with finding evidence that would provide a historic basis for her life’s work, the con man and his obsession with making a name for himself, and Sabar’s obsession with tracking down the story. It makes for a compelling and surprisingly fast-paced read.

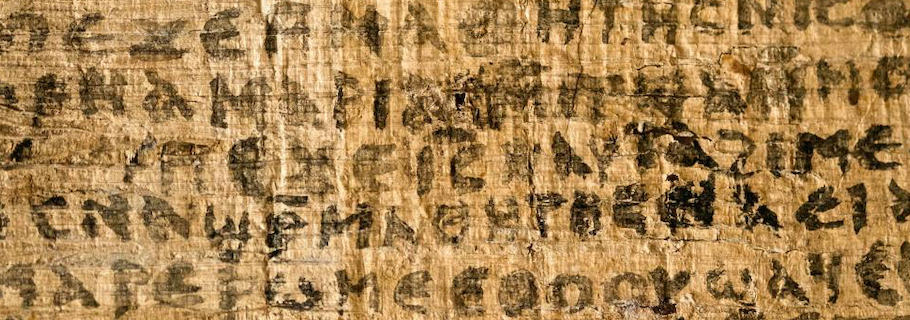

In 2012, King announced to the world that she had acquired a fragment of papyrus that would change everything we thought we knew about the Christian faith. She called it The Gospel of Jesus’s Wife because the fragment, written in Coptic, had Jesus referring to Mary Magdalene as “my wife.” This was a triumph for King who, in these words, saw the vindication of her conviction that the truth about Jesus had been covered up by the first Christians and thus misunderstood for the subsequent 2,000 years. Media around the world breathlessly covered the story and it was quickly headline news.

The fragment was small, about the size of a business card, and both worn and frayed by age, but it contained enough words that King confidently connected the dots in such a way that she constructed an entire narrative around its existence. In its content she saw a massive correction of faulty Christian doctrine.

King’s conjectures were informed by years of scholarship, and she alchemized them into a case for a thoroughgoing Gospel of Jesus’s Wife, a hypothetical codex originally written in Greek within 170 years of Jesus’s death and spanning some untold number of pages, then copied two centuries later into Coptic, from which only the present, minuscule fragment survived. Some thirty Coptic words on eight discontinuous lines—in the middle of a random page of unknown size—were all King needed to summon a powerful narrative: Jesus’s male followers challenge Mary Magdalene’s qualifications for discipleship, but Jesus sets them straight, calling her “my disciple” and “my wife,” wishing ill on her critics, and teaching the spiritual meaning of marriage. From thirty words on eight disconnected lines King had extracted a fully realized story, with setting, conflict and resolution—beginning, middle and end.

Of course so great a discovery would arouse the interest of a vast array of scholars, and it took only hours for many of them to express their concerns about very nearly everything—the fragment’s acquisition, its provenance, its authenticity, its translation, and its interpretation. Many of them were immediately convinced it was a forgery. For a long time King kept the fragment closely guarded so few experts could examine it. But various people studied images of it, pondered what King had said about it, and began to pull the pieces together. They found errors in the syntax, they found that its wording closely matched existing Gnostic gospels, they found that its lettering was too poorly written, they found that its translation seemed to rely on a uniquely quirky and uniquely faulty amateur interlinear edition of The Gospel of Thomas. Mostly they found that it made no sense. Yet King dug in.

As a reporter assigned to the story, Sabar was there from the beginning. And as the story developed he stuck with it. Increasingly suspicious of the fragment’s authenticity, he began to deepen and widen his investigation, and it eventually led him to a Florida man named Walter Fritz. Fritz was a failed scholar and shady businessman who had most recently turned to producing pornography with his wife. (And here I must warn that the book contains descriptions of that pornography that are undoubtedly more graphic than necessary; those parts can be skipped without significantly impacting the book.) Fritz was a sexual deviant, compulsive liar, and very possibly a thief and sociopath who also had an interest in antiquities (plus a single semester of Coptic). While he only ever owned up to being the one who provided the papyrus to King, it became increasingly obvious that he is also the one who forged it. And, in what seems to have been a pattern in his life, he did poor quality work. To date, nearly every expert who has examined the fragment has determined it is a fake. And not only is it a fake, but it isn’t even a particularly good one.

So why did King fall for it? And why did she double-down even in the face of such harsh criticism from such noteworthy experts? Why did she stake her reputation on something that was so obviously fraudulent? Essentially because she so badly wanted it to be true. Having spent her whole career teaching facts that could not be defended by the historical record, she saw her chance to finally offer solid proof. But here she was willing to pragmatically stretch the meaning of “truth” so a fiction could be true if it advanced something she believed in enough. Says Sabar, “What fired her intellect was the papyrus’s text, its story—a narrative that amplified her long-standing views about women’s wrongful exclusion from the Church, a lullaby that filled a long-lamented lacuna. Whether or not the Gospel of Jesus’s Wife was authentic, it had what King’s mentor, Bob Funk, called ‘operational effectiveness.’ It felt true to many people’s experiences today. It was an entrée—a business card, in both size and function—to authentic but longer and more complicated texts, like the Gospel of Mary and the Diary of Perpetua, with which King earnestly wanted believers to engage. It was a parable with the power to improve lives.”

And this leads to a key insight. King had spent her academic career exposing the widely-accepted facts of the Christian faith as false. Even as a “Christian” scholar she told people to set aside their faith to focus on facts, for she judged the former inferior to the latter. But her actions proved that she wanted it both ways. “She sought to expose the Church’s ‘facts’ as positions while promoting her own positions as facts. She needed a double standard—one that permitted stories she judged virtuous to pass as true, regardless of the underlying evidence, while denying the same to narratives she found unethical or ‘operationally ineffective.’ … She demanded that people be ‘accountable’ to facts and history, though she herself believed in neither.”

Veritas makes for an interesting read, but also one that has lessons for each one of us. It shows the reality of confirmation bias, that we are all prone to see and understand things as we wish them to be instead of as they really are. It shows that we should always be guarded, patient, and appropriately skeptical when new discoveries claim to undermine the orthodox Christian faith (as with The Gospel of Jesus’s Wife) and equally when new discoveries claim to support it (as with the James Ossuary). It reminds us that many of the world’s most prominent “Christian” scholars hate the Christian faith and actively oppose it through their teaching and research. And it calls us not to be people of a double standard, not to be people who will be swayed or motivated by “operational effectiveness,” but only ever to be people of the Truth.