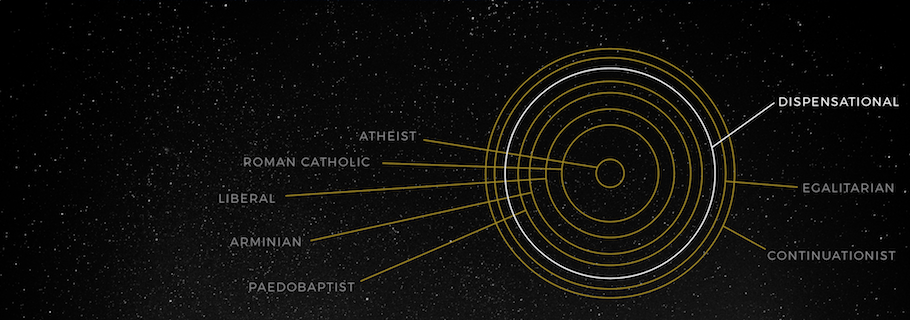

As you know, I am well into a series that tells what I believe by discussing the things I do not believe. To this point I have told why I am not atheist, Roman Catholic, liberal, Arminian, or paedobaptist. That means we are hastening toward the end of the series with just three articles remaining. Today I will tell why I am not dispensational, and I warn you in advance, it may prove disappointing. Each of us has areas in which our theological convictions are deeply developed and others in which they are not quite so much. In this area I have not carried out the same level of study as, for example, the doctrines of salvation or scripture. My convictions are developed but not nearly as much as I might hope and, indeed, as you might hope.

If you are still reading after that warning we will move on to definitions. All Christians profess with the Apostle’s Creed that at some point in the future Christ will come “to judge the living and the dead.” But exactly how and when this will unfold are matters of intense and ongoing debate. This field of study is called eschatology which Greg Allison says “covers the return of Christ and its relationship to the millennium (amillennialism, postmillennialism, premillennialism) and the tribulation, the resurrection, the last judgment, the eternal blessing of the righteous and the eternal judgment of the wicked, and the eternal state of the new heaven and the new earth.” In other words, eschatology is the study of what’s next and of what’s last.

Dispensationalism is a kind of framework for history that is organized around seven dispensations—seven orders or administrations. Particular to this framework is the eschatological position known as “premillennial dispensationalism” which holds that Christ will return prior to a literal one-thousand-year reign on earth. When I say I am not dispensational, this is primarily what I mean—I do not hold to premillennial dispensationalism. Allison points out “It differs from historic premillennialism by its belief that prior to the tribulation, Christ will remove the church from the earth (the rapture); thus, it is also called pretribulational premillennialism. Revelation 20:1-6 pictures Christ’s rule over the earth (while Satan is bound) for a thousand-year period, which is followed by Christ’s ultimate defeat of a released Satan, the last judgment, the resurrection of the wicked, and the new heaven and new earth.”

As I’ve mentioned before, most of my childhood was spent in Dutch Reformed churches and Dutch Reformed schools (despite, as I’ve also mentioned, my complete lack of Dutch heritage). This means I was raised on a steady diet of the Heidelberg Catechism which my parents supplemented with the Shorter Catechism. Neither one of these documents places much emphasis on the end times. For example, the Westminster simply asks, “In what does Christ’s exaltation consist?” and answers “Christ’s exaltation consists in his rising again from the dead on the third day; in ascending into heaven; in sitting at the right hand of God the Father; and in coming to judge the world at the last day.” There are no follow-up questions about that coming judgment. Most who treasure these catechisms adopt amillennialism or postmillennialism and, indeed, I was raised amillennial. It was my understanding that the world will continue roughly along its current tragic trajectory until, at last, Christ returns. (Allison: “With respect to eschatology, the position that there is no (a-) millennium, or no future thousand-year period of Christ’s reign on earth. … Key to this position is its nonliteral interpretation of Revelation 20:1-6: Satan’s binding is God’s current restraint of him, enabling the gospel to advance everywhere. Saints who rule are Christians who have died and are now with Christ in heaven. At the end of this present age, Christ will defeat a loosed Satan, ushering in the last judgment, the resurrection, and the new heaven and earth.”)

The first I ever heard of an alternative was through Christian music. In my teens I began to listen to Petra and though I discovered them in the Beyond Belief era, I eventually went back and bought their older albums. There I encountered songs like “Gonna Fly Away,” from their 1974 self-titled debut. It is hardly brilliant songwriting, but does discuss Christians being removed from the earth while non-Christians remain.

Dreamin’ about flyin’ since I was a boy

Never thought I’d see the real McCoy

I think it’s safe to say, I finally found a wayGonna fly away

Gonna fly awayEvery day I’ve been looking in the sky

Hope it’s not raining when I start to fly

I bet you think I’m strange, wait until I’m changedWhere you gonna be when the trumpet blows?

All that’s left of me is gonna be my clothes

I’d really like to see, you flyin’ next to me

Dispensationalism was going to have a long uphill climb if it was ever to displace my latent amillennialism.

It wasn’t until twelfth grade that I actually met someone who held to this position and could explain it to me. I heard her explanation—rather a good one, I think—but couldn’t reconcile it with my understanding of the Bible. I realized quickly that premillennial dispensationalism was going to have a long uphill climb if it was ever to displace my latent amillennialism. To this day it never has.

So why am I not dispensational? I’d like to say that I have studied the issue very closely, that I have read stacks of books on eschatology, and that I can thoroughly defend my position against every alternative. But that’s not the case. It’s more that my reading of the Bible, my years of listening to sermons, and my study of Christian theology has not been able to shake or displace the amillennialism of my youth. To the contrary, it has only strengthened it. Paul Martin’s recent sermon series through Revelation strengthened it all the more. The very framework of dispensationalism appears to me to fall into a similar category as paedobaptism in that they both, in the words of Tom Hicks, “wrongly allow the Old Testament to have priority over the New Testament.”

While I am not dispensational and do not hold to premillennial dispensationalism, I do wish to express my love and respect for many who hold this position and especially to John MacArthur who has been as important as anyone in forming and shaping so many of my convictions. I am thankful that this is one of those issues in which Christians can joyfully agree to disagree.