It is impossible to consider the modern history or contemporary state of Christianity without accounting for the sudden rise, the explosive spread, and the worldwide impact of Pentecostalism. To that end, I’ve been reading several books on the subject, focused especially on the Azusa Street Revival, which most historians consider the setting in which Pentecostalism began. Here are a few key points I’ve learned about the Azusa Street Revival and the Azusa Street Mission that housed it.

Its roots were in the Holiness Movement. The roots of the Azusa Street Revival and the Pentecostalism it birthed are entwined with the Holiness Movement of the late nineteenth century. This was a renewing movement within the Wesleyan tradition that emphasized complete sanctification and taught that moral perfection is available to Christians. It was marked by a heavy emphasis on personal holiness, most often displayed through a close adherence to the law as a means of drawing near to God. In general, early Pentecostal theology took Wesleyan theology as its starting place, then added to it certain new elements.

It was led by William Seymour. The Azusa Street Mission was led by William J. Seymour, an African American son of former slaves who was born and raised in Louisiana. In his early twenties he traveled to Indianapolis where he had a conversion experience at a Methodist Episcopal church. He left that tradition, though, after becoming convinced of premillennialism and special revelation. He likely migrated to a group called Evening Light Saints where he was exposed to their policies of non-sectarianism, non-creedalism, and equality between races and genders, all of which he adopted and promoted. Though he felt the call to ministry, he battled it until he contracted smallpox and came to believe this was God’s chastisement for his disobedience.

It built upon a previous movement. Though it’s fair to say that the Azusa Street Mission marked the beginning of Pentecostalism, William Seymour had based much of his doctrine and certain of his practices on Charles Parham. Parham had become convinced that Christians needed to rediscover the miraculous spiritual gifts, especially that of tongues. These tongues would allow mission work to advance in foreign lands and help usher in the Lord’s return. Parham founded a Bible school in Topeka, Kansas, where in 1901 one of his students received the Holy Spirit and spoke in tongues. Though Parham was an unabashed racist and unorthodox in many key doctrines, Seymour studied at his college for a short time—enough to absorb his view of the ongoing spiritual gifts. Seymour was soon called to a church in Los Angeles and left Parham, whom he was soon to eclipse as the father of Pentecostalism. Parham seems never to have forgiven Seymour for this.

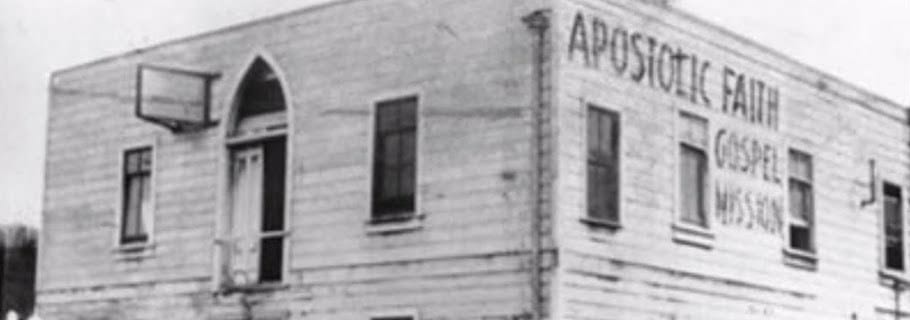

It began near Azusa Street. The Azusa Street Revival actually began in a small house on nearby Bonnie Brae Street. On April 9, 1906, Seymour was three days into a ten-day fast with several other people (all of whom were African American), when he laid hands on one participant and prayed he would receive the Holy Spirit. That man fell to the floor, then began to speak in tongues. They hurried to the house of Richard and Ruth Asberry on Bonnie Brae Street where others were waiting. Soon many of them had a similar experience of Spirit baptism and also spoke and sang in tongues. This drew the interest of neighbors and within days the house became so packed that they were forced to move to the nearby vacant building at 312 Azusa Street. (That building has since been torn down, but the house on Bonnie Brae Street remains as a museum.)

It was distinctly egalitarian. From its very beginning, the Azusa Street Mission permitted both men and women to fill all positions of leadership, including preaching. The revival was also racially egalitarian, so that whites and minorities worshipped together in a way that many at the time considered scandalous. Some of the early critiques of the movement ooze with malicious racism as onlookers express their revulsion with black men worshipping alongside white women. The multi-ethnicity of the earliest Pentecostals contributed to what would become Pentecostal worship, which absorbed elements of various cultural traditions. (Seymour would later amend his views to allow only men to hold certain leadership positions.)

It was a revival of a particular view of sanctification. The Azusa Street Revival was not first an evangelistic movement, though some people did claim to be saved through it. Neither, like the Great Awakening, was it marked by people coming to a deep awareness of their sinfulness. Rather, the reviving that took place was predominantly sanctification and the baptism of the Holy Spirit. This sanctification was according to the Wesleyan definition of “Christian perfection” or “entire sanctification”—an instantaneous act that was to be pursued after justification as a second act of grace. Where justification saved the believer, sanctification cleansed him. To this Wesleyan theology, the early Pentecostals added a third experience, the baptism of the Holy Spirit. This was not an act of grace, but an act of empowerment in which the Holy Spirit made the person particularly useful to Christian service.

Its most noteworthy characteristic was speaking in tongues. The defining experience of those involved in the Revival was the baptism of the Holy Spirit, and the essential mark of that baptism was speaking in tongues. In the early days, these tongues were thought to be human languages and some went so far as to attempt to write them in foreign scripts (much to the glee of the media). It would take months or even years before they came to understand these tongues were not human languages. In the meantime, they had sent scores of missionaries to foreign lands, convinced they had been given the gift of the local language. It was only subsequently that they developed a theology of tongues that would account for the speaking of angelical or prayer languages.

Its worship involved more than speaking in tongues. For the first two or three years of the movement, there were three services each day at the Azusa Street Mission, so the building was constantly full of people engaging in many forms of worship. While speaking in tongues was one of the marks of worship, there was far more to it. Cecil Robeck says, “While the mission valued and celebrated spontaneity, every service also included the predictable. There were public prayers, singing, testimonies, preaching or teaching from the Bible, and time spent around the altar or in one of the upstairs rooms in personal prayers.” Some of the Pentecostal worship was readily identifiable to any Christian of any tradition, while some was new and unique. Gaston Espinosa insists that Seymour’s “main message was not tongues, missions, nor end times eschatology, but rather that a person must be born-again to go to Heaven.” With this being true, tongues did play a key role as the necessary mark of one who had been filled with the Spirit.

It spread rapidly. The Revival sparked a movement that spread with startling rapidity first across Los Angeles, then through America, and into the rest of the world. Many of those who spent time at the Azusa Street Mission “caught the fire” and took it to their own churches in their own cities. Many others took it overseas so that within months its influence had extended to distant lands. It would very quickly take root on every continent and, in many places overwhelm existing works to become the foremost expression of Christianity.

It was undermined by bad eschatology. The leaders of the movement were convinced that speaking in tongues stood as proof that the Spirit was beginning to work in a fresh way that foretold the imminent return of Christ. This added an urgency to the movement that often overwhelmed reason and discernment. So missionaries were dispatched to foreign lands without preparation, without any view to biblical qualification, and without any thought as to when and how they would return. They claimed God had gifted them with that foreign language, they claimed to be called, they believed Christ was about to return, so they were duly sent—sometimes within a matter of days or even hours after being baptized in the Spirit. Not surprisingly, this often proved disruptive and destructive to work already underway in the foreign nations.

It collapsed through scandal and infighting. Though Seymour was able to lead the Mission, he proved unsuited to lead the movement. Some of those who attempted to do so on his behalf betrayed him or sought to displace him. The Oneness movement, which insisted that baptism should be only in the name of Jesus, splintered Pentecostalism. One of his closest co-workers absconded with the mailing list through which Seymour had disseminated his influence throughout the world. William Durham attempted to integrate a more Calvinistic view of sanctification into early Pentecostalism and drew away many of Azusa’s people. The movement also began to experience disruptions along racial lines and Seymour attributed this largely to the prejudices of white people who wanted to take over the work. He responded by decreeing that no white person could be in leadership until the racial climate had improved. The early unity quickly gave way to all manner of scandal and infighting.

By 1908 the Mission had begun to wane. By the end of 1909 there was little doubt that it had gone into serious decline, just three years after it had begun. But, of course, Pentecostalism survived and thrived. Today there are 500 million people in the world who identify as either Pentecostal or Charismatic and, to some degree, all of them can trace their roots to Azusa Street.

(These are the facts. At some point in the future I’d like to bring some analysis of those facts. Sources: William J. Seymour and the Origins of Global Pentecostalism; The Azusa St Mission and Revival.)