I recently returned from a whirlwind visit to Rome where I was conducting research related to a forthcoming project. Though I was not in the city for long, I made the most of it and over two long days journeyed hither and yon, tallying a little over 50 kilometers (31 miles) of walking. I rate the trip a success for the most part and hope to disclose more about my project in the near future.

As I was preparing for the trip, I found myself wondering: Could there be anything related to Protestantism in the world’s most Catholic city? Feeling mischievous, I did some research, talked to a few people in the know, and decided to go looking. Though it was slim pickings, the things I did find fascinated me. What follows is a list of four things my fellow mischievous Protestants ought to look for while visiting the city of Rome. And even if you do not have the opportunity to visit, you can still see the pictures and read the descriptions of Protestant history in Catholicism’s capital.

1. Scala Sancta

The Scala Sancta, or sacred steps, figure prominently in both Catholicism and Protestantism. For Catholics they remain a place of pilgrimage and, for locals at least, are nearly synonymous with Lent. But for Protestants they are a relic of history, for they played a key role in the consternation and conversion of Martin Luther.

When Christ was on trial, he was led up the steps of Pilate’s palace to be condemned. Though these steps were originally in Jerusalem, legend tells that St. Helena, the mother of newly converted Emperor Constantine, ordered them brought to Rome around 326 AD. At some point they were reassembled there and pilgrims began to climb them as a sign of contrition and as a means to gain God’s favor.

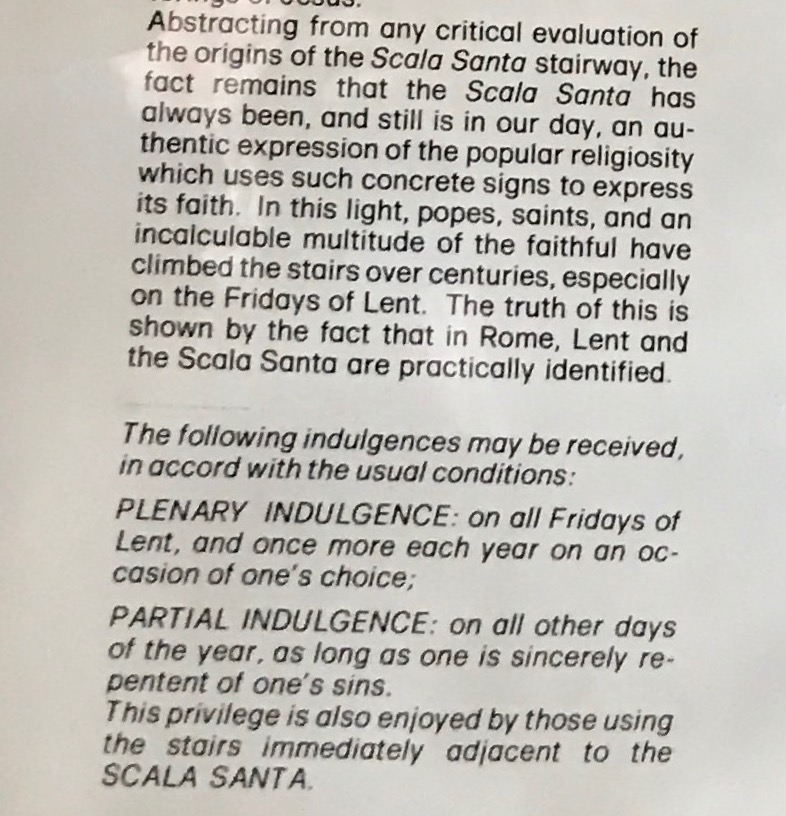

The steps are currently housed in the Pontifical Sanctuary of the Holy Stairs, which is across the way from the massive Archbasilica of St. John in Laterano. Enter the building and there they are, just a few feet from the entranceway. Three signs are prominently posted inside the doors. The first forbids taking photos of people on the steps while the second reminds visitors that the steps must be climbed on knee, not on foot. (The photo I’ve used here is an “official” stock photo which I’ve got permission to use.) The third explains that indulgences are granted to those who climb the steps while they are sincerely repentant of their sins. There are plenary indulgences for climbing them on the Fridays of Lent and once more per year at the time of the climber’s choosing. There are partial indulgences for other days of the year or, I suppose, for the person who climbs them more than once in a year. An indulgence, as you know, is a remittance of any punishment in purgatory due to sins that have been committed and confessed.

I stood for a while and watched people from around the world climb mournfully and painfully, pausing on each step to pray a “Hail Mary” or “Our Father.” Then I thought of Luther who, centuries ago, climbed those very steps as a faithful son of the Church, but without any assurance that his contrition was sufficient. He went through the motions but could never gain assurance that his penitential actions were properly motivated. The Scala Sancta represented an important milestone along the road to Reformation because Luther’s failure to find assurance drove him to the Bible for a more satisfying understanding of the work of Christ. What he learned is that we cannot ascend to Christ; rather, Christ must descend to us.

2. Chiesu del Gesù

Now we move from a flight of stairs to a pair of churches, and it must be said that these are not Protestant churches. To the contrary, these are churches of The Society of Jesus (or Jesuits), an order that was founded during the Reformation to defend the Catholic faith against the heresy of Protestantism. Each of the buildings contains something that should be of special interest to Protestants.

The Chiesu del Gesù (Church of Jesus) is the mother church of the Jesuits. For such a noteworthy building, its exterior is quite unadorned and there are just two figures on its front, Jesuit co-founders St. Francis Xavier and St. Ignatius of Loyola. Each of them stands with a foot upon an anonymous heretic, Xavier upon an impassive man and Loyola upon an undignified woman whose breast protrudes from her dress. Loyola clutches a book and points to it with his opposite hand while Xavier holds aloft a branch. Each wears a stern but confident expression, for they are doing the Lord’s work of crushing those who dare oppose his Church.

Catholic churches of this magnitude are typically constructed in a cross shape with a large hall that runs the length of the building and a number of chapels lining each side. Gesù follows that classical pattern, and two of its chapels stand out in importance. The chapel in the right transept (arm of the cross) is the Chapel of St. Francis Xavier. A towering painting by Carlo Maratta, difficult to see in the dim light, displays the saint’s death. Beneath it, rising above an ornate altar, is a seventeenth century silver reliquary holding Xavier’s left arm. It is said that this arm baptized some 300,000 people, making it worthy of veneration. The rest of his body is enshrined in India. Today many people visit the chapel to kneel, to light a candle, to pray, and to seek the intercession of this revered saint. I spoke briefly with an Indian pilgrim who joyfully told of how he had now seen all of St. Francis, having previously visited Goa during one of the rare occasions in which the church there uncovers the body.

Opposite this is the chapel of St. Ignatius of Loyola. Once again, a giant painting dominates the chapel, this one equally difficult to see unless the light is just right. The work of Andrea Pozzo, it shows Ignatius receiving the standard from Christ. Far beneath it is a gilded bronze coffin containing the saint’s remains. Unbeknownst to most visitors, the painting is rigged with a mechanism that lowers it at 5:30 each evening to display the huge silver statue of Ignatius that stands in the alcove behind it. For the few minutes before this, spotlights shine on the painting, allowing for much better views.

On either side of the altar are large and intricate statues. To the left is “The Triumph of Faith over Idolatry,” the work of Jean-Baptiste Theodon. Here a king and peasant woman are being trodden upon by a woman who is either Mary or the Roman Catholic Church. She holds aloft a golden chalice while underfoot the king and peasant look up in awe and terror. With her left foot she crushes the neck of a terrible dragon. In this vivid image we see the triumph of the church over idolatrous kings and commoners.

The second statue is by Pietro Le Gros and titled “The Triumph of Faith over Heresy.” Here Mary holds a flame in one hand and a cross in the other while cradling a book in her arm. Two men lay at her feet, crying out in fear and agony. In fact, they are beneath her feet as if they are tumbling through the earth and down to hell. Both are in the clutches of a vicious serpent who falls with them while nearby, an angel tears pages out of a book. Who are these people and what is the book?

The two men in this statue are Martin Luther and Jan Hus, so it seems likely that the angel is destroying their unauthorized vernacular translations of the Bible. Several books and a scroll lay on the ground, and a zoom lens can pick out the words on their covers: “Mart Luther” on one and “Joann Calvin” on the other. Here is the Roman Catholic Church triumphing over the Protestant heresy. Or, from a Protestant perspective, here is Catholicism mobilizing and militarizing to persecute those who dare preach the gospel of grace alone through faith alone, for the Jesuits were to become like an army, their priests called “God’s Soldiers” and their leader “Superior General.” Through their zealotry and absolute loyalty to their faith and their pope, they were to bring great suffering to God’s people.

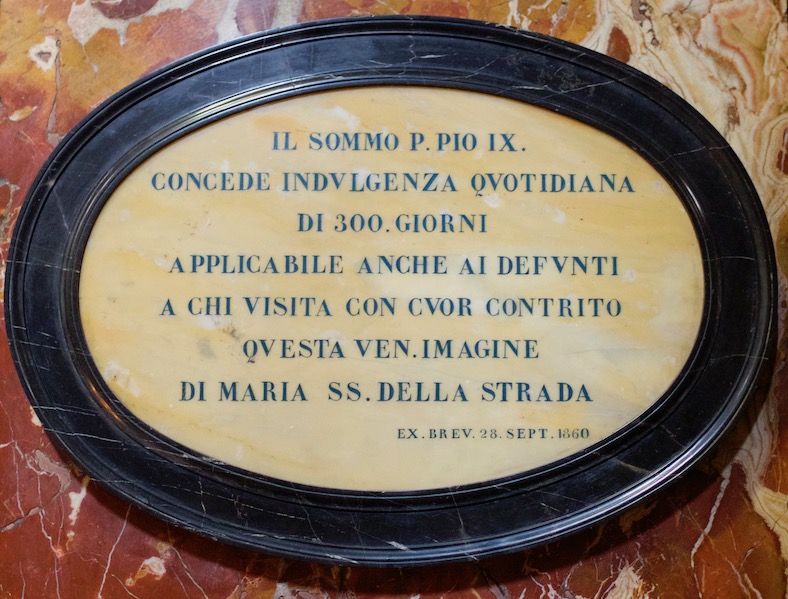

Also of interest and in ironic proximity to the Reformers, is a small placard affixed to the wall between this chapel and the one beside it. Beside the Chapel of St. Ignatius, in the church’s left tribune, is the Chapel of Santa Maria degli Astalli. Within this chapel hangs Santa Maria della Strada, a fourteenth century fresco depicting Mary and Jesus that is said to have been especially precious to Ignatius. The placard announces that, by order of pope Pius IX, a 300-day plenary indulgence is granted to anyone who visits the chapel in a contrite spirit. Alternatively, the indulgence can be applied to a deceased loved one. For a full hour I sat in the church and observed. Many people, most of them priests, knelt before the coffin of Ignatius to contemplate and to pray for his intercession. Many more walked into the chapel to claim their indulgence. All the while, the presence of Luther and Hus contrasted powerfully with the empty hope of indulgences and the vain petitions to a dead saint.

(If you visit this church on a Saturday or holiday, you may explore a little museum that contains a number of valuable items. Also, next to the church is a second museum that will lead you through the rooms of Ignatius which contain a number of his personal effects.)

3. Chiesa di Sant’ Ignazio di Loyola

The Church of St. Ignatius of Loyola is less magnificent than its older sister, though they both counter Reformation simplicity with their ostentatious baroque styling. Only a visit can do justice to the interior art, especially upon the expansive ceiling. A magnifying mirror helps display its detail.

Of far more interest to me than the art on the ceiling was the contents of the left tribune. On each of the corners of that little room is a statue of one of the four cardinal virtues, but far more prominent is a great plaster statue of Ignatius, a copy of an original that is with St. Peter’s Basilica. His right hand is stretched out, palm toward the sky, and in his left he clutches a book with two pages open. The first is emblazoned with the Jesuit symbol and the motto “Ad Maiorem Dei Gloriam,” which translates to “for the greater glory of God.” The second says, “Constitutiones Societait Iesu” indicating that the book is Loyola’s Constitution of the Jesuit Society.

Beneath Loyola’s left foot lies a man, his face contorted in agony. The first finger of one hand is clenched between his teeth while in the other he grasps a closed book. A serpent twists and writhes around him. Once again, this man is Martin Luther. The book in Luther’s hand may be his unauthorized translation of the Scriptures, or it may be a broad representation of all his writing. Either way, the point is impossible to miss. Here, too, we see the Counter-Reformers identifying their enemy, mocking and warning the man and his followers, and displaying their confidence that they will gain the victory. It is noteworthy that Loyola’s book is open while Luther’s is closed.

Each of these churches, then, reminds us of how the Roman Catholic Church responded to the Reformation. Though the Church may be far more diplomatic today, we do well to remember that she prides herself on being “semper eadem,” always the same. What the church condemned then, she condemns now—unchanged and unchangeable.

4. Campo de’ Fiori

The last stop is a monument in Campo de’ Fiori, a market square. If you visit while the market is active, you will need to find your way past the vendors and street performers to find the monument rising up in the middle of the square. There you will see a bronze statue of the heretical philosopher Giordano Bruno emblazoned with an inscription that, translated, declares, “To Bruno – the century predicted by him – here where the fire burned.” His face forever in the shadow of his hood, he gazes defiantly in the direction of the Vatican. On the base of the monument, which was erected in 1889, you may spot several large medallions, each with a face carved upon it. Each of these represents another philosopher or theologian who was persecuted by the Catholic Church. Circle around and you may spot two faces that look familiar—John Wycliffe and Jan Hus. You may also spot a couple who are less familiar but equally important, the Italian Reformer Aonio Paleario and the French Protestant Petrus Ramus.

Beneath Wycliffe and Hus is a bronze relief of Bruno being burned at the stake on this very spot, for it was here, in the Campo de’ Fiori, that he and many heretics were burned. While Bruno is considered a martyr of science, there were many Protestants who were likewise put to death right here. The two forerunners of the Reformation and their French and Italian brothers stand in for many other believers who lost their lives for refusing to recant their faith.

Is There More?

There is probably more Protestant history than this, and if there is, I would be glad to hear of it. Certainly there is plenty of early-church history which is also worth seeing. And most people will wish to visit St. Peter’s Basilica to consider the role indulgences played in its construction. (Also, consider the layout of St. Peter’s, and how it’s “arms” welcome all people and draw them in, but then face them with the imposing building which represents the power and authority of the Church.) But the four I have listed at least represent a good place to begin for mischievous Protestants who wish to see Rome.