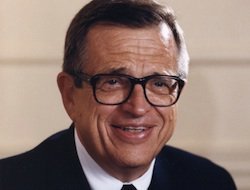

I don’t mean to be a curmudgeon and I don’t mean to be insensitive, truly. Perhaps there are rules that govern these things, and I am violating them, or maybe I am just missing some vital piece of information. I don’t know. But I have been to a wide variety of Christian blogs and news sites reading the obituaries and memorials and remembrances of Charles Colson and have been surprised to note that they are have been very nearly uniformly, unabashedly positive.

I don’t mean to be a curmudgeon and I don’t mean to be insensitive, truly. Perhaps there are rules that govern these things, and I am violating them, or maybe I am just missing some vital piece of information. I don’t know. But I have been to a wide variety of Christian blogs and news sites reading the obituaries and memorials and remembrances of Charles Colson and have been surprised to note that they are have been very nearly uniformly, unabashedly positive.

I am not convinced that we are doing right here. I suppose I would rather wait a little while to say this, but then the opportunity will be gone. At least to my understanding, Colson’s legacy was both more and less than people are making it out to be. I didn’t really understand the man in all his inconsistencies and complexities while he lived–the combination of good and bad baffled me–and I certainly don’t understand him now that he has died.

Don’t hear me say that Colson was a complete villain, but do hear me when I say that he leaves behind a legacy that is far more multi-faceted, far more multi-dimensional, than most people have been saying. It is a legacy that includes some dark chapters, and not only prior to his conversion.

Charles Colson leaves behind a testimony of a man who encountered grace at his darkest hour. He leaves behind a legacy of a ministry that seeks to extend grace to those who are likewise in their darkest hour. He sought to teach Christians how to think–to describe and define a biblical worldview. And then he sought to lead in the application of that biblical worldview, and this is where things become hazy, where a positive legacy collides with a woeful one, where his work for the Lord encounters his work against the Lord’s church.

He labored for good and positive causes, but he also labored for outright sinful causes.

The fact is that as we remember this man, we remember someone who labored to strike a significant blow against the gospel, and who time and again called on the church to do the same. And this is what is absent in so many remembrances. He labored for good and positive causes, but he also labored for outright sinful causes.

Colson was a leader, a co-founder, of Evangelicals and Catholics Together, one of the efforts that must stand as part of his defining legacy. At heart, ECT made the Reformation a mistake or an over-reaction and sought to draw Protestant and Catholic back together. It made little of the gospel, suggesting that there was no unbridgeable difference between the gospel of the Reformation and the gospel of Roman Catholicism. This had potential to do terrible damage to the church and its gospel witness. Remarkably, the obituary at The Gospel Coalition mentions ECT along with Colson’s other accomplishments as if it is substantially the same as Prison Fellowship. Most others do not mention it at all.

R.C. Sproul wrote two powerful and important rebuttals to ECT, Faith Alone and Getting the Gospel Right, books that are still well worth a read today. Time may have dulled our collective memories, but in its time ECT was a major issue and a major threat to church unity and gospel centrality. It was just the kind of threat that merited and demanded the treatises Sproul provided–ones that sounded a warning and drew attention to a danger that so many people were ignoring.

Then there was the more recent Manhattan Declaration, another effort to form a wide ecumenism. This Declaration addressed critical issues of our day: the sanctity of human life, the dignity of marriage as the conjugal union of husband and wife and the rights of conscience and religious liberty. But it did so as Evangelicals and Catholics and Orthodox together under the banner of a common gospel. John MacArthur said it well in an article detailing why he would not sign his name to it:

It assumes from the start that all signatories are fellow Christians whose only differences have to do with the fact that they represent distinct ‘communities.’ Points of disagreement are tacitly acknowledged but are described as ‘historic lines of ecclesial differences’ rather than fundamental conflicts of doctrine and conviction with regard to the gospel and the question of which teachings are essential to authentic Christianity. … [It would] relegate the very essence of gospel truth to the level of a secondary issue. That is the wrong way—perhaps the very worst way—for evangelicals to address the moral and political crises of our time.

Sproul likewise declined to put his name to the Declaration. At heart it downplayed the gospel to a lowest common denominator. It used the word gospel as if it applied in the same way to Roman Catholics and Protestants, something very consistent with what Colson held and taught throughout his years of being a leader within Evangelicalism.

In these ways and others, Colson undermined the gospel.

In these ways and others, Colson undermined the gospel. He may not have set out to do this and he may not even have understood that he was doing this, but it remains the fact of the matter. ECT and The Manhattan Declaration stand as two prominent and public testaments to his willingness to tamper with the purity of the gospel. These things really happened and they both had the potential to be very, very destructive to the church because each one called into question the gospel, the very heart of the Christian faith.

It is not wrong of us to mention these negative aspects of his legacy along side the good. They are nothing more, nothing less, than what is true of the man. As Christians we ought to be able to deal with a mixed legacy, one of success and failure, one that is as complex and inconsistent as so many men are. Our worldview ought to be big enough to deal with such things. To portray Charles Colson as all villain is unfair to the man; to portray him as all spiritual giant is unfair to the church. Let’s not be afraid to call it as it is.

Note: For some reason the commenting script has disappeared. I’m trying to restore it.