Self-salvation is sinful man’s most natural inclination. We all know there is something wrong with us, that we are not all we want to be and not all we were meant to be. And left to ourselves we look for that salvation anywhere and everywhere except in the place it can be found–in Jesus Christ.

Self-salvation is sinful man’s most natural inclination. We all know there is something wrong with us, that we are not all we want to be and not all we were meant to be. And left to ourselves we look for that salvation anywhere and everywhere except in the place it can be found–in Jesus Christ.

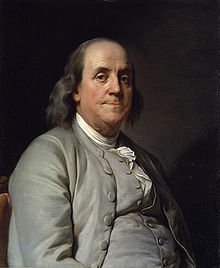

I recently came upon a great illustration of this in the life of Benjamin Franklin. Come Christmas or birthdays or other occasions, I love to buy my parents biographies; they are adept at finding the most fascinating facts and anecdotes and it was my mother who dug this one up in Walter Isaacson’s life of Franklin.

Franklin was a Deist. He held to the existence of some kind of higher power, but believed that this God had created and then retreated, that he was not personally present in the world. If this is the case, all we can know about divinity and humanity will be revealed through nature and reason. Franklin had no use for Scripture or worship and certainly no use for Jesus Christ beyond personal example.

Franklin believed “The most acceptable service to God is doing good to man.” Yet when he was still young he “came to the conclusion that a simple and complacent deism had its own set of drawbacks. He had converted Collins and Ralph [two friends] to deism, and they soon wronged him without moral compunction.” He began to see that Deism accounted for the existence of a God, but not an ethic that would transform behavior. He wanted to better himself and do good to man, so systematized his approach.

On the pages of a little notebook, he made a chart with seven red columns for the days of the week and thirteen rows labeled with his virtues. Infractions were marked with a black spot. The first week he focused on temperance, trying to keep that line clear while not worrying about the other lines. With that virtue strengthened, he could turn his attention to the next one, silence, hoping that the temperance line would stay clear as well. In the course of the year, he would complete the thirteen-week cycle four times.

He wanted to improve himself, wanted to be good. He was willing to admit fault with himself, rather a rare trait, and to work to improve those shortcomings. And so he arrived at a orderly way of pursuing his goal. He would identify and quantify his faults in order to grow in virtue.

What was the result? It was the result any honest man would come to. “I was surprised to find myself so much fuller of faults than I had imagined.” His honesty and consistency conspired to leave little doubt of his propensity toward outbursts and, therefore, away from the temperance he desired. A year would not be nearly enough to see substantial advances. “In fact, his notebook became filled with holes as he erased the marks in order to reuse the pages.”

What was the result? It was the result any honest man would come to. “I was surprised to find myself so much fuller of faults than I had imagined.” His honesty and consistency conspired to leave little doubt of his propensity toward outbursts and, therefore, away from the temperance he desired. A year would not be nearly enough to see substantial advances. “In fact, his notebook became filled with holes as he erased the marks in order to reuse the pages.”

Franklin is describing a universal experience here: the experience of frustration and despair. We can almost hear his echo of the Apostle Paul who, centuries earlier, had written, “I do not understand my own actions. For I do not do what I want, but I do the very thing I hate” and “I have the desire to do what is right, but not the ability to carry it out.” In his despair Paul cried out, “Wretched man that I am! Who will deliver me from this body of death?”

Jesus Christ had been good for him and could now be good through him.

His question found an immediate answer. “Thanks be to God through Jesus Christ our Lord!” Paul’s despair was met in Jesus Christ. Paul could not be good on his own, so he looked for help outside himself. The solution would be extrinsic, not intrinsic. Jesus Christ had been good for him and could now be good through him.

But Franklin admitted no Savior, no God who was personally present in his world, so he had no choice but to look within and to continue his efforts. With his notebook full of holes, rubbed through by all these evidences of his depravity and inability, he bore down all the more. “He transferred his charts to ivory tablets that could more easily be wiped clean.”

When his efforts led to failure, he simply redoubled his failing efforts. He might wipe those tablets clean, but they too would do nothing more than highlight his inability to wipe himself clean. His efforts at self-salvation would ultimately, inevitably prove futile.