This morning I am thrilled to bring you a guest article from my friend Tim Keesee of Frontline Missions and the excellent DVDs Dispatches from the Front. This is an article he prepared in honor of John Bunyan’s birthday on November 28.

On the Rail near Bedford, England

Beads of rain race along my window as my express train speeds through the mist back to London. My mind and pen are racing, too—I have seen and heard so much in Bunyan’s Bedford.

From that lonely cell came one of the greatest books

Took a train this morning to Bedford to walk where John Bunyan walked—for him it was a path of suffering that included 12 years in prison for Christ’s sake. Yet from that lonely cell came one of the greatest books, The Pilgrim’s Progress. After more than three centuries, it lives on in over 200 languages worldwide. But it’s more than a book—it’s Bible and biography in one. It smells of the dungeon and glows with the Gospel. I recall during the Soviet times seeing underground printed copies of The Pilgrim’s Progress—the treasured pages bound by hand, and the boards covered with wallpaper. With so much love and risk wrapped up in that dangerous volume, it was a book that could rightly be judged by its cover.

Bunyan’s book has blessed the world, but in Bedford, little remains from his life and long imprisonment. The church meeting place in his day was a barn where Dissenters worshiped. It has long since been replaced by a beautifully-appointed chapel with a museum next door. In the garden between them, the remains of those who heard him preach rest beneath moss and marble. The home Bunyan shared with his wife and children—which stood for over three centuries—could not stand up to a bulldozer when “progress” came rolling through a few years ago.

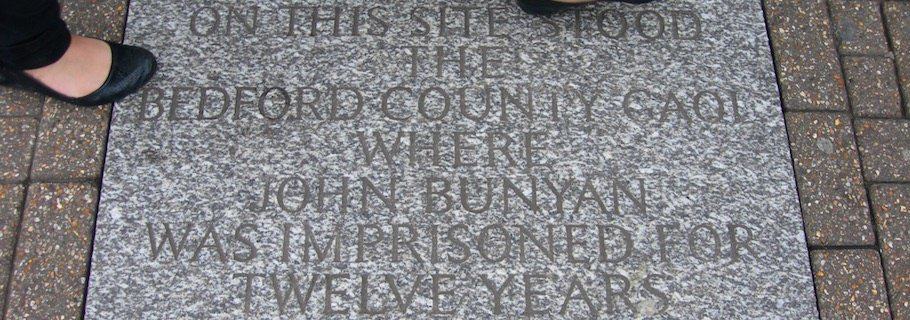

A minute’s walk from Bunyan’s church, the site of his jail is marked by a sidewalk tablet. The pavement is pocked with gum and crowded with shoppers hurrying past. I expect most of them are ignorant of the one who from that very spot wrote, “The parting with my Wife and poor Children hath often been to me in this place as the pulling of the Flesh from my Bones.” At any moment Bunyan could have walked out a free man—all he had to do was promise not to preach. But this he could not do.

The charges against him in 1660 were precisely what house church pastors in China, Vietnam, and across central Asia face right now—holding “illegal meetings.” But John Bunyan had to preach the Gospel—not in defiance of men but in devotion to God. It was a calling that would cost him dearly, especially in the separation from his wife and four children, including a blind daughter. In his spiritual autobiography, Grace Abounding to the Chief of Sinners, Bunyan wrote from prison,

I found myself a man encompassed with infirmities; the parting with my Wife and poor Children hath often been to me in this place as the pulling of the Flesh from my Bones; and that not only because I am somewhat too fond of these great Mercies, but also because I should have often brought to my mind the many hardships, miseries and wants that my poor Family was like to meet with should I be taken from them, especially my poor blind Child, who lay nearer my heart than all I had besides; oh, the thoughts of the hardship my poor Blind one might go under, would break my heart to pieces… yet, recalling myself, thought I, I must venture you all with God, though it goeth to the quick to leave you. O, I saw in this condition I was as a man who was pulling down his house upon the head of his Wife and Children; yet, thought I, I must do it, I must do it.

The years passed, and so did Pilgrim’s trials—the Hill of Difficulty, the lions, the wounds of Apollyon, the chains of Giant Despair, and finally through dark water to the Celestial City. It was a path that Bunyan knew very well—and a way already worn by nail-scarred feet. This hard, lonely place was once made brighter by “the fellowship of His sufferings.” There in Bedford Jail, Bunyan wrote and worshipped in pain and took comfort in His company.