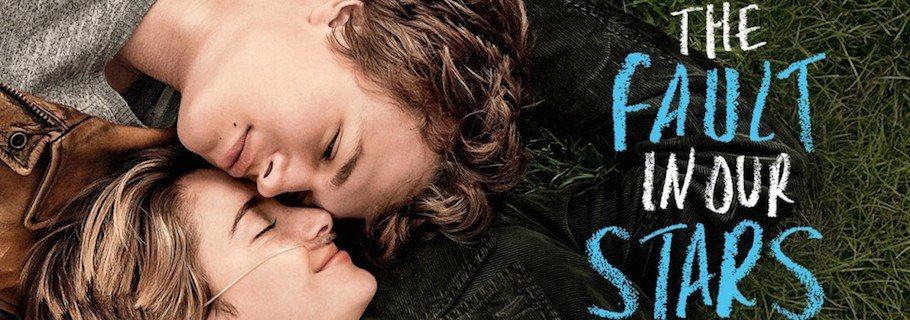

It has nineteen thousand reviews on Amazon, with an average rating of five stars. I try to keep up with what’s new and notable in publishing but even with nineteen thousand reviews I had no intention of reading this novel until both my son and daughter (separately) asked if they could buy it. After all, they said, all their friends are reading it. It’s called The Fault in Our Stars and the movie adaptation has just hit the silver screen, opening as the most popular new movie in North America.

(I am assigning this review a full-out spoiler alert; you have been warned.) The Fault in Our Stars centers around two teenaged characters who are brought together in a common battle against cancer. Hazel, who narrates the book, is sixteen and has lungs so badly damaged by cancer that she must always be connected to a source of oxygen. Though drugs are currently controlling her illness, she knows that she has only years, not decades, to live. One day she attends a church-based cancer support group where she meets Augustus who is seventeen and recovering from osteosarcoma.

Hazel and Augustus immediately hit it off and begin a romance centered around Hazel’s favorite book: An Imperial Affliction by the fictional author Peter Van Houten. This book so closely describes her life and condition that she views it as her Bible, the book that best describes reality as she experiences it. Because Van Houten deliberately left the book unfinished, her dream is to go to Holland to meet him and to find closure by finding out what happened to the characters.

As she and Augustus date, we find out that Augustus has an outstanding Wish (granted by a Make-a-Wish foundation) and he uses his wish to take Hazel to Amsterdam to meet the elusive Van Houten. They do meet him and find that he is an angry, raving alcoholic and that they will get no answers from him. They deal with their disappointment by going to a hotel and taking one another’s virginity.

No sooner do they return to America then Augustus finds that his cancer has returned worse than ever. Hazel stays by his side, their love growing all the while, until he dies.

The story isn’t exactly morbid, but it also doesn’t qualify as feel-good literature. I suppose most people probably cry at the end. But as I read The Fault in Our Stars I found it very difficult to understand why so many young people are raving about it. I read Twilight and immediately understood why young women had responded to it so strongly; I read The Hunger Games and immediately understood why both young men and young women enjoyed it. But The Fault in Our Stars? What sets it apart from the billion-and-one other teenage romance dramas? It is much less clear to me.

But I do have a theory. As far as I can see, Green has not written teens as they are, but as they’d like to be perceived. I remember that when I was a teenager I wanted to be taken seriously and believed that big words and deep thoughts would give me a kind of legitimacy I otherwise lacked. And this is what Green does: he creates characters that talk like, well, middle-aged men—characters who have the philosophical background, verbal expression, and vocabulary of people much older than them. The way the main characters express themselves sounds suspiciously like the way a middle-aged man would express himself, and especially so if he was trying to impress everyone else with his deep thoughts and extensive lexicon. I love how this reviewer says it: “The problem is that indicating that your characters are intelligent by giving them all the voice of a 30-year-old Yale English Lit major who is trying to impress a date is not great writing. It is (brace yourselves) mediocre writing that tramples and ignores and substitutes any genuine character voices with your own.” Indeed. And therefore we find Hazel saying things like this:

How did scrambled eggs get stuck with breakfast exclusivity? You can put bacon on a sandwich without anyone freaking out. But the moment your sandwich has an egg, boom, it’s a breakfast sandwich. … I want to have scrambled eggs for dinner without this ridiculous construction that a scrambled egg-inclusive meal is breakfast even when it occurs at dinnertime.

Of course she also speaks about weightier subjects than scrambled eggs, but typically in a similar voice and with similar language.

So my theory is that the real attraction is that the characters think big thoughts. They think big thoughts and use big words and big concepts to express them. Green takes his teenaged characters seriously instead of making them hopelessly shallow and obsessed with trite issues. These aren’t characters from an Archie comic who care only about who dates whom and whose car is the nicest. These are characters wrestling with the big issues of life and death and who are capable of waxing eloquent about them. In fact, in this book the teens are complex and the parents are shallow. In that way its subtly rebellious, an upside down world where the kids get it and the parents do not. Green writes as an adult who is down on adults—as an adult who gives young people what they want to hear.

In the end I would hesitate to recommend The Fault in Our Stars to its intended audience of teens and young adults. Green does offer a lot of interesting insights into morality and mortality and there are some pretty good lines mixed in. “Grief does not change you, Hazel. It reveals you.” “Some tourists think Amsterdam is a city of sin, but in truth it is a city of freedom. And in freedom, most people find sin.” He also ably contrasts Hazel, who is content to die unknown and unnoticed, with Augustus who feels that life is only meaningful if he achieves distinction and notoriety.

And yet it’s not all good. There is a considerable amount of profanity and sexual innuendo, and a surprising number of blends of “god” and “damn.” There is a considerable amount of complaining about authority, defying authority and, of greater concern, belittling it. That extends to the Bible’s authority. At one time Green had apparently intended to be a minister and vestiges of a Christian worldview can be found in the book, but only vestiges. Mostly he teaches—well, I don’t know what he teaches. It’s not nihilism, but neither is it Christian hope and optimism. In a novel about illness and death, he makes suffering meaningless and eternity dubious. Of equal concern is the minor plot line that brings the sixteen and seventeen year-old together in bed. Though it is not particularly alluring or explicit, the moral is that it is far better to find a soulmate and have sex with him or her than die a virgin.

Would I allow my children to read The Fault in Our Stars? I guess it would depend on their age and maturity. I’m certainly not afraid of the book; the message of the gospel is not only far more powerful than what Green presents but also far more hopeful. If they were to read it, I am sure they would quickly spot the contrast between the bleakness of Hazel’s and Augustus’ reality and the hope and joy of the gospel.

(If you have read the novel, and especially if you are a teen who has read the novel, I’d love to hear from you about what you appreciated, and perhaps what you didn’t appreciate, about it.)