No Man’s Sky was supposed to change gaming forever. It was pitched as offering players a vast world with nearly endless opportunities to explore and nearly infinite varieties of planets and life to discover. It promised an incredible 18 quintillion (that’s 18 billion billion) planets to find—far more than a million gamers on a million consoles could ever see and experience. Players imagined dedicating endless hours to exploring, communicating, fighting, and trading their way across its massive expanse. The game was delayed and delayed again until it finally released on August 9, 2016. It landed with a resounding thud. And in that thud we can find a fascinating lesson.

No Man’s Sky

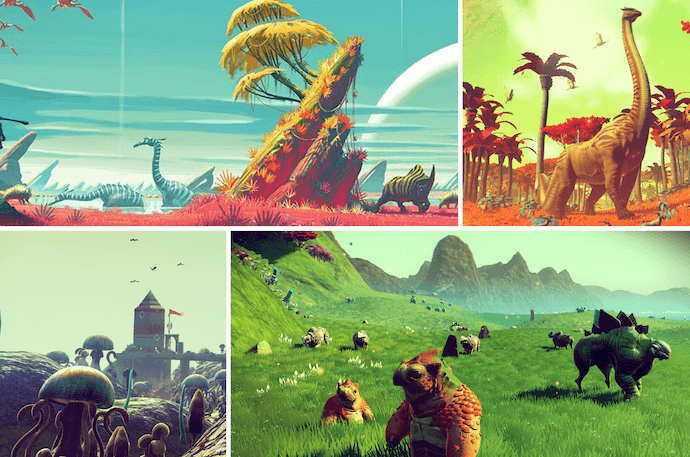

No Man’s Sky’s great claim is that its world is created through procedural generation, “a method of creating data algorithmically as opposed to manually.” Most computer games require a game designer to manually create almost every aspect of its world. They dream it, they plan it, they place each element within it. The sheer effort involved in such work necessarily limits the size of a game and gamers are familiar with running into the edge of playable areas. But procedural generation allows the designer to step aside in favor of algorithms, computer scripts essentially. In No Man’s Sky this algorithm is responsible for generating nearly everything: “star systems, planets and their ecosystems, flora, fauna and their behavioural patterns, artificial structures, and alien factions and their spacecraft.” Early screenshots and demos showed a beautiful world full of interesting planets, unique creatures, stunning vistas. Anticipation was at a fever pitch. Then the game launched.

No Man’s Sky’s early reviews were mixed. Gaming powerhouses IGN and Polygon each assigned it a 6 out of 10, Gamespot and Trusted Reviews a 7, The Guardian and The Telegraph an 8, and Time a 9. The user reviews were far tougher. Just 39% of 36,000 Steam reviews are positive while Amazon reviewers are assigning it an average rating of only 2.9 stars. Recent media reports have focused on the swell of disgruntled customers demanding a refund. A recent Forbes headline declares Gamers Have Every Right To Push For ‘No Man’s Sky’ Refunds.

10,000 Bowls of Oatmeal

A procedural universe may be technically impressive but it is also bland, empty, purposeless.

What went wrong? While reviewers praise the game for its size and scope, its ambition and visuals, and its ability to provide an experience free from obnoxious loading screens, they critique it for being, well, boring. Procedural generation, the very aspect of the game that is meant to make it stand out, has proven to be its greatest weakness. A procedural universe may be technically impressive but it is also bland, empty, purposeless.

IGN says, “The few hand-crafted moments in No Man’s Sky stand out from the bland procedural universe” and “nothing of consequence ever happens in this vast universe. You’re the only one in it with any agenda or power to do anything of significance.” Likewise, Polygon says, “Before you decide whether or not No Man’s Sky is a game you’ll appreciate, you must ask yourself a single tough question: How much do you value technological wonder over everyday, solid, smart game design?” It laments that “these powerful universe creation algorithms have been grafted onto a game that is, beyond its initial hours, so light on imagination.”

Gamespot declares “The sheer number of possible variations of worlds and wild species is too large to fully comprehend, but because the variety is defined by a computer pulling from a restricted pool of options, animals appear more like slapdash creations than thoughtful constructions.” Other users pointed out that many of the algorithmically-generated animals were nonsensical, dumb, impossible. Clearly, the algorithms stand in stark contrast to the few parts of the game that have been carefully designed by human beings. Players find themselves longing for more design and fewer algorithms.

No Man’s Sky is a dud. In the minds of tens of thousands of disappointed gamers it does not live up to its promises. Indeed, it could not because its procedural generation has resulted in a drab world that is full of planets but empty of purpose. Writing for Motherboard, Emanuel Maiberg makes a crucial point. He quotes Kate Compton, an expert on procedural generation, who describes what she calls the problem of 10,000 bowls of oatmeal. Using procedural generation “I can easily generate 10,000 bowls of plain oatmeal, with each oat being in a different position and different orientation, and mathematically speaking they will all be completely unique, but the user will likely just see a lot of oatmeal.” Uniqueness does not necessarily equal interest or purpose and in this way No Man’s Sky’s users put too much hope, too much faith, in procedural generation. They ended up with those proverbial 10,000 bowls of bland oatmeal. Maiberg compares the game to another recent release, a smash hit.

When Sony came to New York to demo No Man’s Sky they also came with a demo for Uncharted 4, which is the exact opposite to No Man’s Sky in terms of design. Uncharted 4, which is made by another studio of about 300 people, is one of the most beautiful, rich virtual worlds I’ve ever seen. Every leaf and stone in it was hand crafted and placed at just the right spot to create the desired effect. It’s a highly directed experience, where the designers are trying to funnel me from point A to B in a way that feels like an exciting, unique experience, but that in reality is identical to the experience of every other player.

The Lesson For Us All

Purpose, meaning, interest, and even true beauty come by the mind and careful crafting of a designer.

There’s something to learn here. A world that is procedurally generated is a world that is bland, repetitive, meaningless, boring. Purpose, meaning, interest, and even true beauty come by the mind and careful crafting of a designer. What is true of the virtual world of No Man’s Sky is equally true of the very real world that we inhabit. If there is evidence of purpose, meaning, and interest in this world—and there is in its every part—it stands as evidence, handiwork, of a designer.

Thanks to Dave Drabiuk for suggesting and requesting the article.